Key Elements of Experiential Learning: What It Is and How It Happens

I once taught a class at a gas station. I was leading a group of undergraduates on a study tour of South Africa. We’d spent the day before with a community of Black South Africans who had successfully reclaimed their land from the white commercial farmers who occupied it throughout the Apartheid era. It was a fascinating day, but at the end of it there was no time to reflect on what we had experienced.

We were scheduled to depart early the next morning, and after several hours of driving, the van needed fuel and the driver needed a break. In a small town along a rural South African highway, we pulled into a gas station that included a grassy area with a couple of picnic tables. This was my opportunity to make up for that missed reflection session.

Like many experiential educators, I’m a constructivist. I believe that meaning is made, not acquired, and so reflection on experience is essential to make it meaningful. Before we reached our next destination, we needed to take time to make meaning out of the action of the previous day, even if there was nothing like a classroom available. While the van driver napped in the grass, my students and I debriefed the experience, made connections to themes emerging in the study tour, and related these ideas and feelings to their growing understanding of themselves as global citizens.

Key Elements of an Experiential Learning Program

Action and reflection are key elements of an experiential learning program, but they aren’t the only key elements. After years of working in international education, I have developed my own acronym for creating effective experiential learning: DPART. It stands for Design, Prepare, Act, Reflect, and Transfer. At Hartford International University for Religion and Peace, I apply DPART thinking at many levels, from individual lesson plans to overall program design. Here’s a quick look at each element:

- Design: As with traditional methodologies, effective experiential learning depends on having a purpose for each activity and knowing how it relates to the larger purposes of the course, program, or institution. The design stage is about generating learning outcomes, about sequencing activities, and planning for the prepare, act, reflect, and transfer stages. Education that is student-centered takes a great deal of instructional leadership, and much of that leadership happens in the design stage.

- Prepare: We need to set students up to learn from experience, and this goes well beyond clarifying logistics and procedures. Preparation takes many forms and can include accessing the students’ prior knowledge, evoking their learning goals, and strategizing for how to meet those learning goals. The amount and type of preparation necessary varies depending on the goals of the activity.

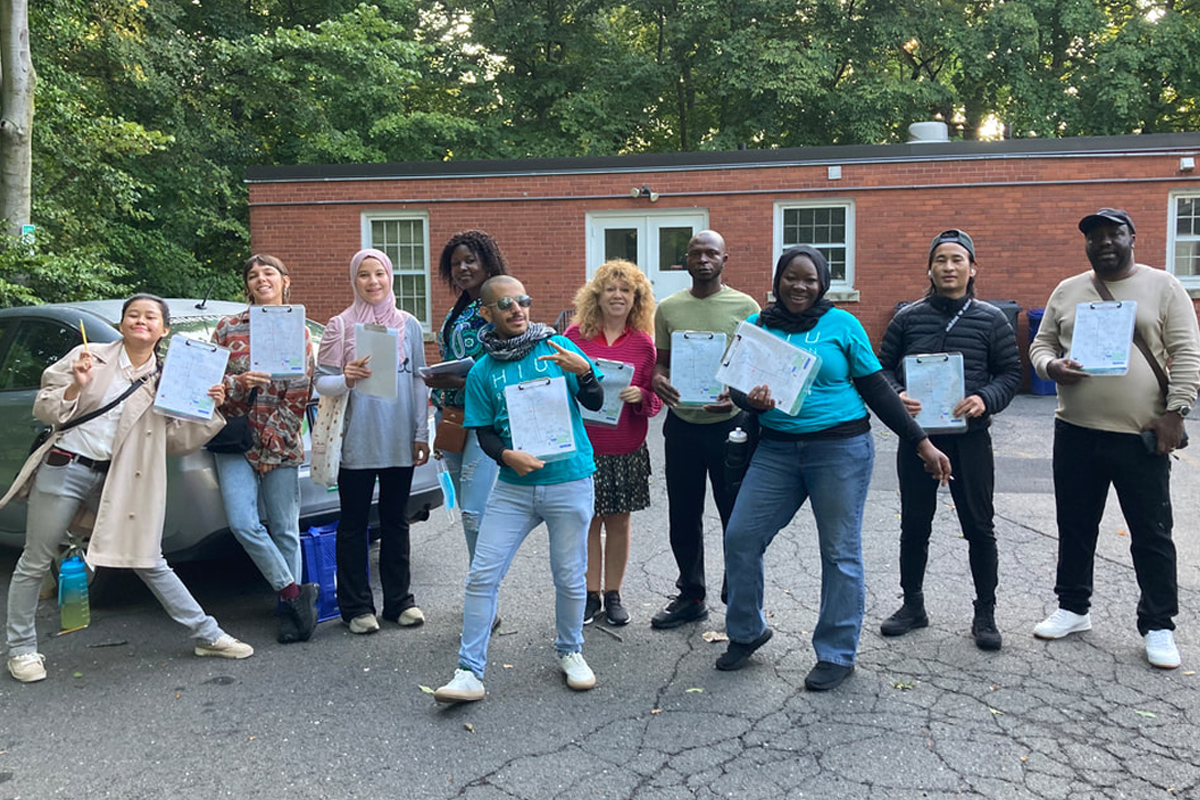

- Act: From an outside perspective, this is what experiential learning is about – students engage in some sort of action, such as a site visit, service work, or role play. However, action does not equal learning without the scaffolding of the other stages. Ideally, experience should involve connecting to personally meaningful goals beyond just getting a good grade.

- Reflect: Students are asked to contemplate the experience cognitively, emotionally, and as often appropriate here, spiritually. Reflection allows students to articulate how the experience relates to (or totally upends!) their prior knowledge and their learning goals. It can also let them work through any strong emotions generated by the experience.

Transfer: Finally, students are asked to identify connections between what they learned from the experience and their larger personal, professional, and/or religious lives. With experiential learning, the goal is not just knowledge but often changes in thinking, feeling, or behavior. This is hard work and requires an intentional focus on how their learning will impact them beyond their time in the current educational setting.

I use DPART to organize both small and large aspects of the MA in Peacebuilding program (MAP). For a single role play in my Constructive Conflict Intervention class, I design the role play to challenge students around a particular mediation skill related to our course learning outcomes. We prepare with pre-meetings among the mediators and among students playing each party in a conflict to strategize how that skill will be tested in the role play. The role play is the action, and afterwards we always debrief, both in small groups and as a whole class. Debriefing incorporates both reflection and transfer, as students process the experience and recognize the potential impact on how they handle real conflict in their own lives.

DPART also informs the whole arc of the MAP program. We have designed learning outcomes that support the mission of HIU and built an intensive program to promote student mastery of those outcomes. Students are prepared for their one-year MA in many ways, including an intensive course on Introduction to Peacebuilding prior to the start of the fall semester. Action and reflection happen continuously through their coursework and field work. They complete their degree with a capstone project designed to transfer their interreligious peacebuilding skills back to their home communities.

Experience alone is not experiential learning. DPART gives me the framework to ensure that all the time and effort dedicated to experience actually results in learning.

Photo credit: Aida Mansoor

Tags: key elements of experiential learning in international peacebuilding