Experiential Learning in Peacebuilding: Preparation Is Essential

I’m not a fan of throwing students into the deep end.

Experiential Learning is essentially learning through doing and then reflecting on that activity. Often jumping right into an activity, interaction or experience is seen as the natural starting point for experiential learning. I’m an experiential educator, but that’s not how I run an experiential education program, and my unwillingness to start with experience puts me at odds with many of my peers.

David Kolb, an eminent theorist of experiential learning, grounded his experiential learning cycle in concrete experience, followed by multiple stages of reflection. His theory, first published in 1984, is still hugely influential. Google “experiential learning” and Kolb’s cycle is usually the first, second, and third thing you will see. It isn’t a bad theory, and it comes with an appealingly tidy graphic. It is, however, missing an important part: student preparation for experience.

Preparation is Essential

The longer I teach, the more I think preparation is essential, and modern neuroscience has my back on this. In recent years neuroscientists have come to understand the importance of salience for learning. Salience is the quality of being particularly noticeable or important, and it is related to retention and motivation in learning processes. In every moment there is more going on around us than we can actually absorb. The brain processes stimuli to prioritize some and downplay others. Students need cueing to attend to what is most significant. This is particularly true if you are going to bring them into some novel kind of experience. This cueing – or framing – happens through preparation, and it can take many forms, such as:

- Activation of prior knowledge,

- Eliciting student’s learning goals,

- Setting the tone with warm-up exercises,

- Use of communication agreements to govern interaction,

- Strategizing for how to get the most out of an experience.

Not every experience requires all these forms of preparation! However, most experiences require some aspect of preparation.

Experiential Learning Frameworks

I have borrowed and adapted literacy expert Donna Ogle’s KWL strategy for use in experiential learning. KWL stands for Know, Want to Know, Learn. Originally designed to help new readers make meaning out of texts, I use it as a framework to evoke students’ prior knowledge related to an upcoming experience and then use that as a springboard into what the group wants to learn from the experience. We plan how we will engage in the experience to meet those learning needs.

Post-Experience Reflection

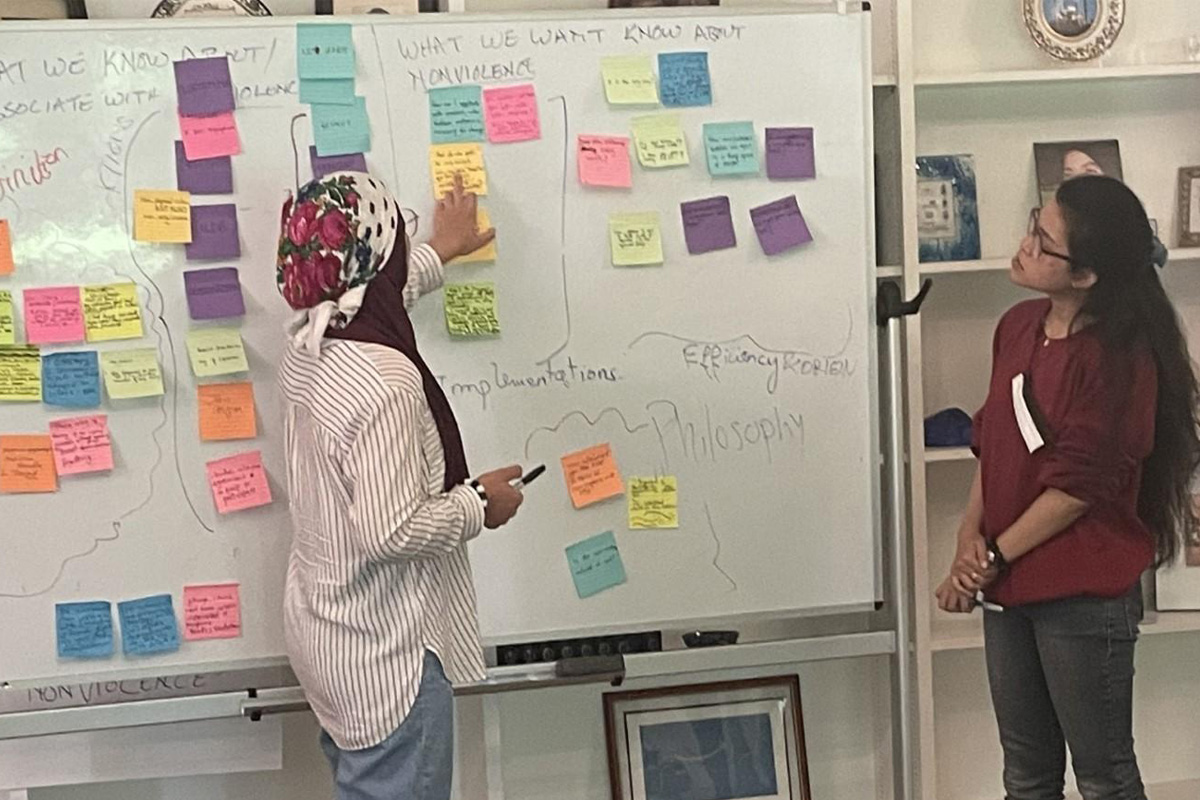

As part of post-experience reflection or debriefing we evaluate whether we learned what we set out to learn. (Sometimes the answer is “No” – which is always interesting to explore.) In the photo, you see MA in International Peacebuilding students preparing for a workshop on nonviolence. The sticky notes on the left of the whiteboard come from their brainstorming and categorizing what they already know about nonviolence. The sticky notes on the right side represent questions they are developing around what they want to learn from the workshop. This preparation helped students to engage deeply in the workshop and led to a rich reflection session the following day.

When we expect students to participate in some new kind of activity without preparation, we throw them into the deep end of the pool. True, some will do just fine. Others will gasp and flail because of an overwhelm of new or upsetting stimuli. Others will swim in circles because they can’t tell where they should be going. Proper preparation gives students the cueing they need to respond effectively to the new experience leading to better learning. Everybody makes it to the side of the pool – wet, possibly cold and tired, and with a better understanding of the water.

Experiential education is an essential element of the MA in International Peacebuilding program at HIU. Students gain knowledge and skills through role plays, case studies, field work, workshops, and projects. Since MAP is a one-year MA program, time is always tight and it can be tempting to skimp on the preparation phase of experiential learning in order to cram in more experiences. I’ve learned to resist that temptation because the time spent in preparation maximizes the learning potential of each activity.

At the end of the year, students return to their home countries ready to implement community-level interreligious peacebuilding projects. The program’s experiential learning model, with its emphasis on practical application of new knowledge and skills, means they go home knowing they are ready for this important work.